So it’s been a long while since I’ve made updates to this blogpost. Being bogged down with schoolwork, exams, and other stuff, plus struggling to finish adding font and audio features have made getting this whole project done an uphill battle. However, the project is at the finish line, and I’m preparing a version 1.0.0 of the framework before I intergrate it to the game engine. Before all of that however, it’s time for me to catch up on all of the changes I’ve made since then, and some new additions as well.

CPP-ifying the Application class

Just to catch up, in the original version of the framework, in order for the user to maintain privacy and encapsulation, the user would have to store their external data in an external class or struct and store a reference to it in the userData field of the App class as a void* pointer, and then whenever a function was called, the pointer could be converted from a void pointer dereferenced to obtain their exteral class instance inside the game loop functions. To learn more in detail about how that worked, check this post here.

This was a pretty C-like way to do things, and while it worked, I felt like I could do something a bit more convenient and one that didn’t require the user to have to dereference a pointer everytime they wanted to access class data and functions. So instead, I decided to make the Application class abstract, and have the user implement all of the virtual functions attached to it. That way, the Application class instance can still be passed to an external build function that runs the app, and enables encapsulation of everything, including hiding private fields.

I also decided to create a seperate function from the init() function called config() so that instead of having to pass an AppConfig to configure the game’s window inside the main() function, they can do it inside the extended app class. This also solved another problem that it’s impossible to do stuff like load textures and create default shaders in the init() without the window being created first, so the two were seperate so that functions dependent of GLFW/GLAD can still be called in the init() function.

Message Logging

This is the only thread-unsafe part of the framework, and it still can be made thread-safe with some basic mutex-locking on the developer’s part. I wanted to make the logger public and universal since it really just exists for the purposes of debugging and can be disabled in Release builds. I also wanted the user to be able to do whatever they wanted with logger information by setting a log callback. This not only gives users control over logging, but also makes it easy to disable since the logger callback could just be set to a function that does nothing at all.

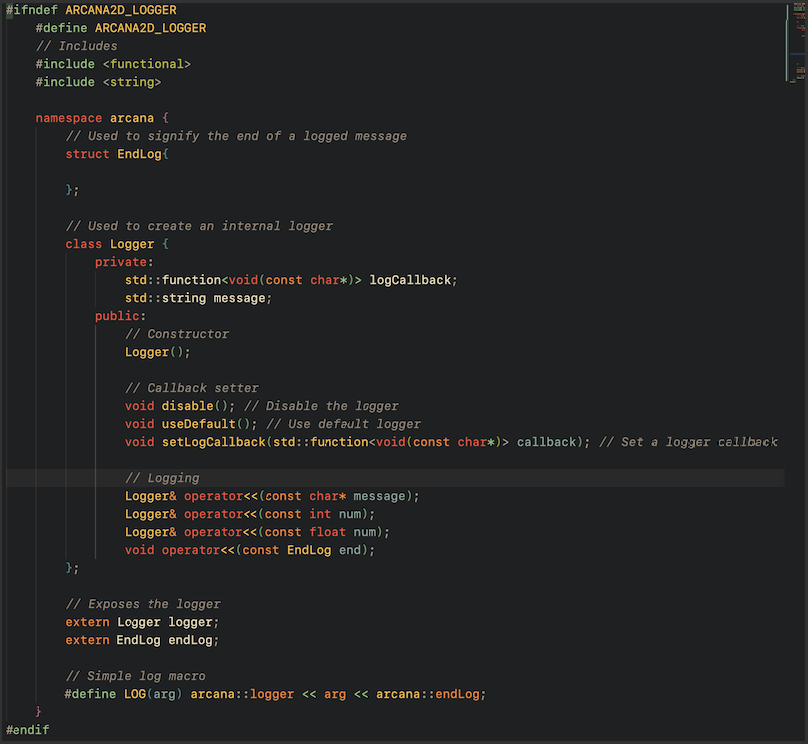

My end result looks something like this:

This is just what the header file exposes. I’ll try to break down what’s happening here.

First, there’s a Logger class. It simply just stores a function that the logger uses for logging messages. These messages are buffered in a string, which is the

messagefield. Also similar tocoutandcinin C++, it uses bit shift operators to send data to the logger. I used this because it’s a nice and easy to use format in my opinion, one that C++ developers should be familiar with using. Essentially, the user adds data to the logger using bit shift operators, then adds aLogEndobject to tell the logger when it is done receiving information, after which the message is converted to aconst char*and sent to the log callback function.The empty

LogEndstruct simply exists just to tell the logger when to stop logging. That’s it’s only purpose.Also, you’ll notice that there are two external variables, one for the logger and one for the

LogEndobject. I got this idea from howstd::coutactually works, because that is an external variable as well. Theexternexposes the internal logger so other parts of the program can easily log messages without needing to create their own instances of each object.

And that’s how the logger works.

Rendering sprites

First, I had to figure out how to render both sprites and primitives using the same shader, because I didn’t want to have to compile two of them. To answer that, I shamelessly stole this idea from the Raylib code, which involves creating a 1x1 white pixel as a default texture that primitives will be drawn with, essentially making them all sprites. All primitives will preserve their own color when drawn with the white pixel, so that problem is solved.

And to be honest, there really wasn’t much more to drawing sprites. Since I had never been used to working with sprite rendering, I expected there to be a lot more involved with the process. But in reality, the main hurdle was simply figuring out how to integrate that with my existing renderer.

Well, that’s most of what I have to say this time around. With my workload, it’s gonna be tough to finish the framework soon, but since I’m nearly there, it shouldn’t be too much of a hassle. Well, till next time!